Author’s Note

The major sources for this article are the 9/11 Commission Report and Commission Staff, Team 7, Monograph, “Staff Report, August 26, 2004.” All times are Eastern Daylight Time (EDT).

Introduction

This is the second of a series of three articles discussing the attack on September 11, 2001, and its aftermath, as a military action. In the first article we discussed the attack in terms of the classic principles of war. In this article we examine the components of the attack in military terms. We begin, however, with a principle we have not discussed, one that overarches the classic principles.

It is a military imperative that the odds of success in battle are improved by getting within the decision cycle of the opponent. Staying inside the cycle, once there, is added exponential value. The 9-11 attackers did all that, not once, but twice.

Decision Cycle Successes

Strategically, the attackers were always well within the decision cycle of the government bureaucracy. The attack came during the transition from one administration to another. Such transitions move forward by fits and starts as a new administration grapples with the policies and priorities of the old order as they fit or, more likely, do not fit well with the policies and priorities of the new order. What to do about counter-terrorism and the emerging threat of the spring and summer of 2001 was just one aspect of the transition.

The details of the transition period are well covered in the reports of both the Congressional Joint Inquiry and the 9/11 Commission. Both the Inquiry and the Commission found that a key transition meeting concerning the terrorist threat was scheduled for September 12, 2001. The attackers were within that decision cycle by one day.

Tactically, the attackers were also well within the decision cycles of both the operator and the defender of the National Airspace System. The operator, the FAA’s Air Traffic Control System Command Center, moved quickly to a decision to ground all commercial air traffic. Concurrently, the Center moved fitfully to a decision to issue a cockpit warning to commercial aircraft in the air. Both decisions were the right thing to do; both decisions failed to save United Airlines flight 93 (UA93). The attackers were within the decision cycle of their enemy and that advantage held long enough to allow the hijacking of the fourth plane.

The attackers also operated within the decision cycle of the air defenders, overwhelmingly in the attack against New York City, barely so in the attack against Washington, DC.

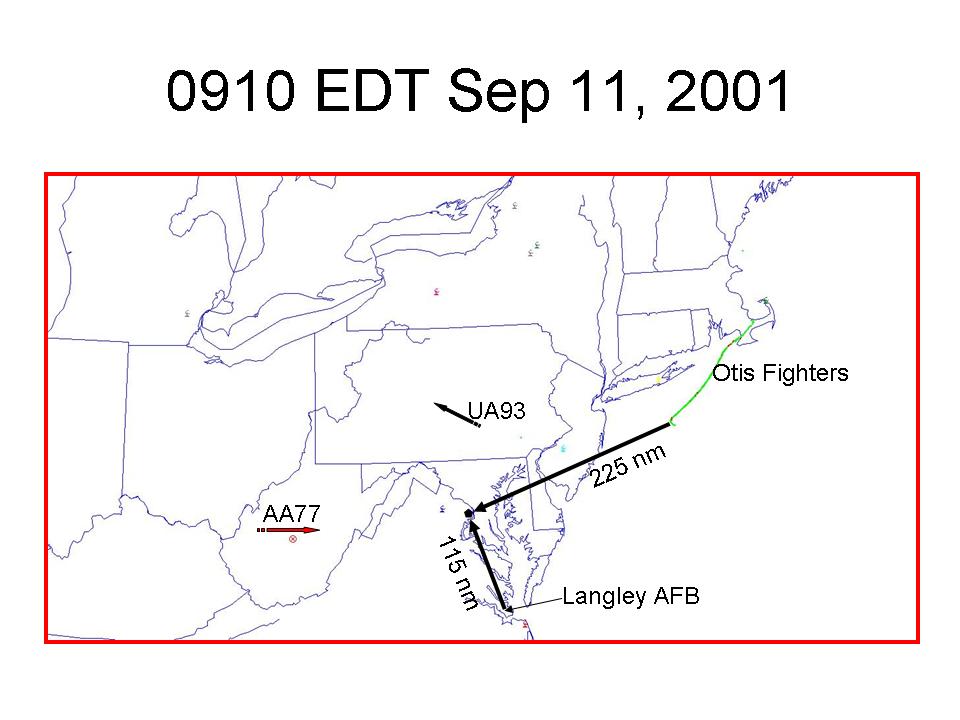

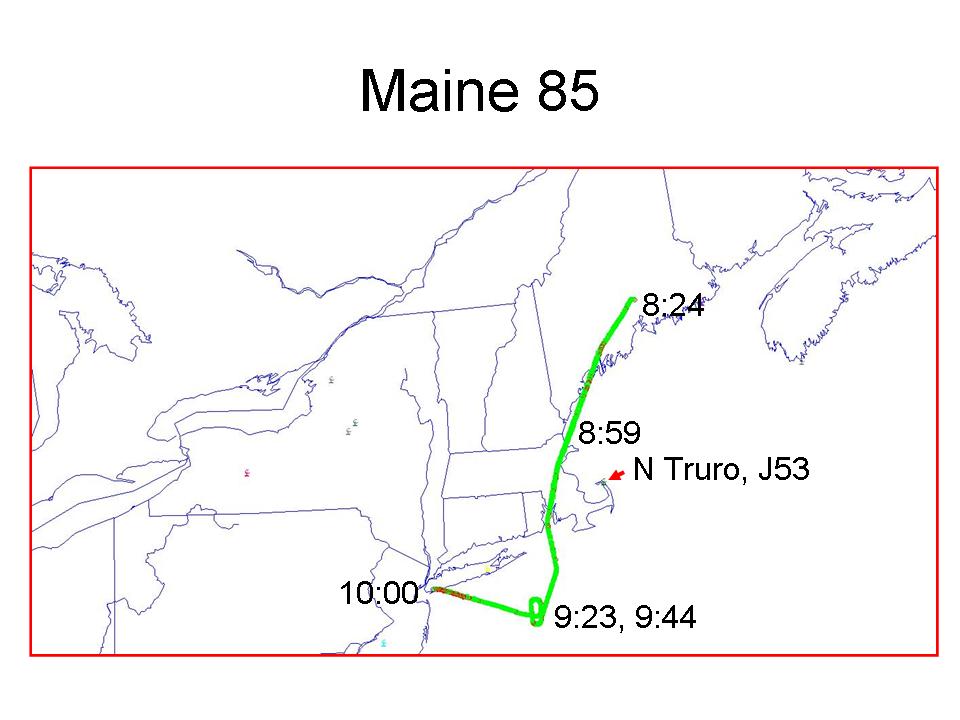

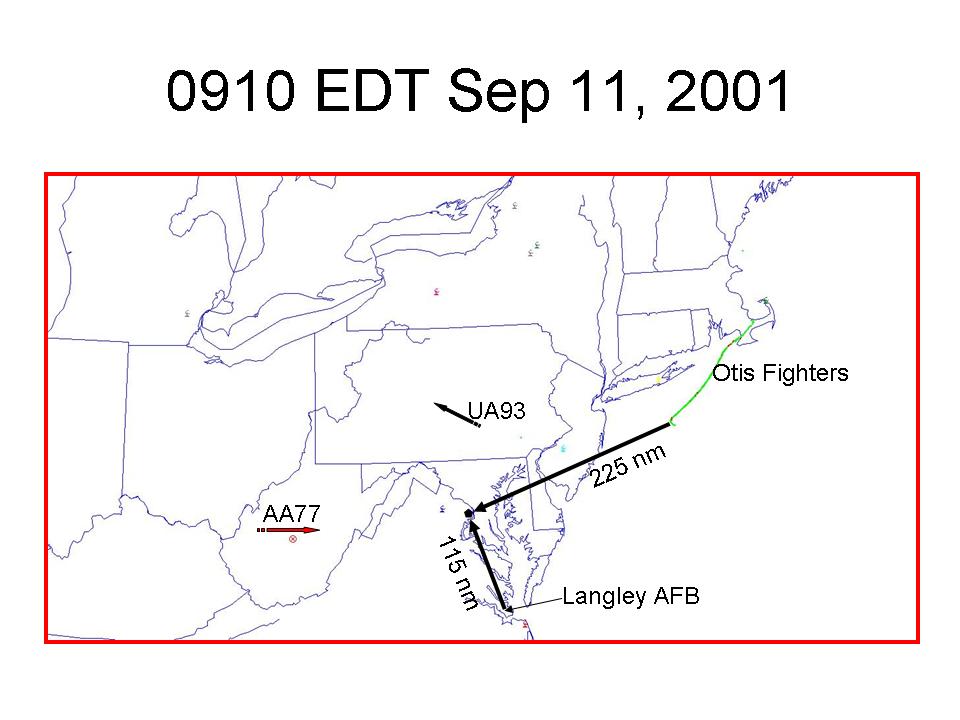

In the chaotic last minutes of the flight of American Airlines flight 77 (AA 77) the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) did acquire the fast moving unknown (AA 77) as a target; to no avail. The Langley fighters, by then airborne, were 150 nautical miles away, over the ocean. The Otis fighters, available if they had stayed in a holding pattern directed by NEADS, were inexplicably over New York City.

The Langley fighters established a combat air patrol (CAP) over the nation’s capital at 10:00 and were well positioned to deal with the approach of UA93. However, they had no authority to engage. That authority did not reach NEADS until 10:31, well after the remaining crew and passengers aboard UA93 took matters into their own hands.

Not only were the attackers within the bureaucracy’s decision cycle, the cycle, itself, was misfiring on all cylinders. It was badly out of tune. With that preamble behind us we now move to what was promised in the first article, a staff officer’s Powerpoint view of the battle.

The Attack

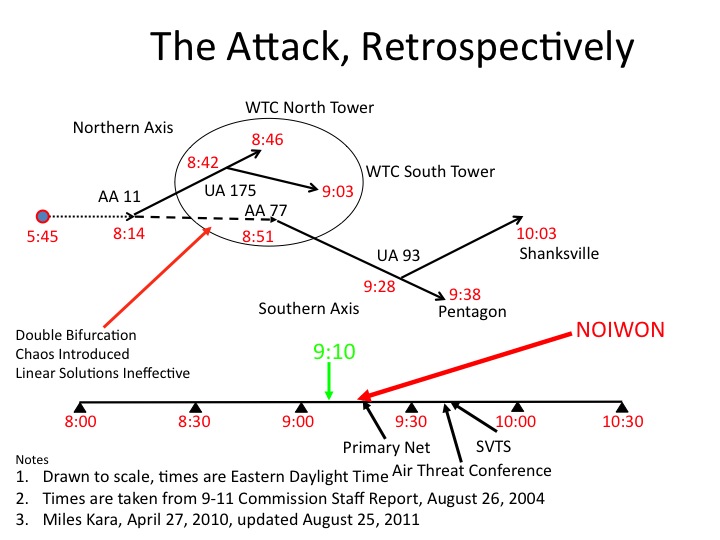

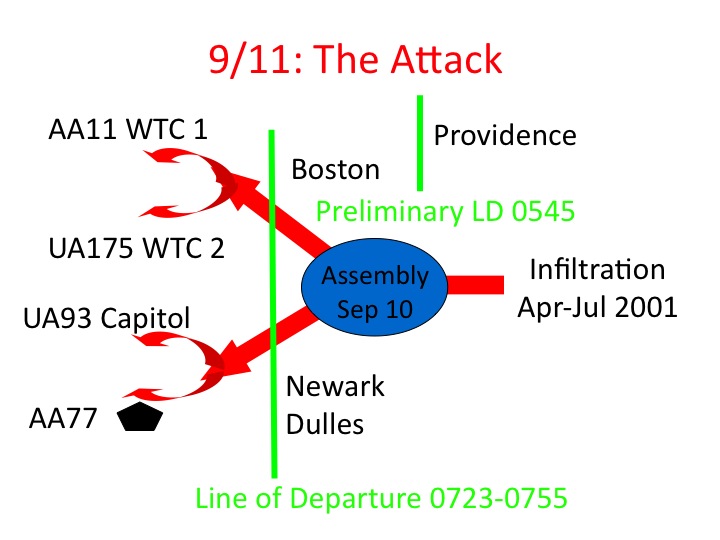

The following graphic was included in a presentation, “It Was ‘Chaos’ Out There,” on November 17, 2011, at The Air Force Historical Foundation and The Air Force Historical Studies Office 2011 Biennial Symposium, “Air Power and Global Operations: 9/11 and Beyond.” I was on Panel 1: “9/11 and Operation Noble Eagle.” Fellow panelists were John J. Farmer, Jr. and Maj. Gen. Larry K. Arnold, USAF (Ret).

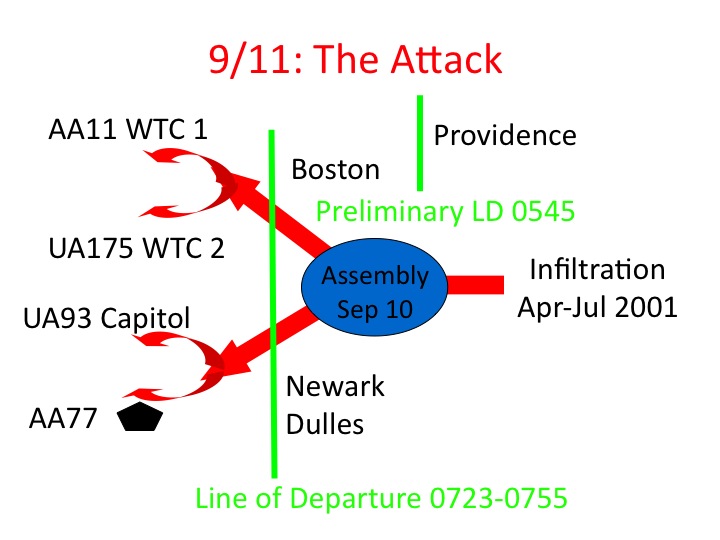

The graphic depicts most of the military components of the attack—infiltration, assembly, preliminary line of departure, line of departure, and attack on two axes of advance, each with two prongs. It lacks one necessary component, the advanced party. We will discuss the battle in terms of the tactical components shown on the slide, but first the advanced party.

Advanced Party

At no time did the advanced party number more than six individuals: the four pilots, Mohammed Atta, Marwan al Shehhi, Hani Hanjour, and Ziad Jarrah; and two long-time al-Qaeda operatives, Nawaf al Hazmi and Khalid al Mihdhar. Here is the story of their arrival in the United States.

It took nearly the entire year, 2000, for the advanced party to establish itself, an activity that spanned the continent and avoided detection. Al Mihdhar and al Hazmi arrived on the West Coast in mid-January. Al Mihdhar did not stick around long, departing for Yemen on June 9, 2000.

Al Hazmi remained until Hanjour joined him in early December, transiting Cincinnati, en route. The two soon moved to Tucson, Arizona in mid-December. This was not Hanjour’s first trip to the United States. He had prior entries in 1991, 1996, and 1997, all without incident.

Meanwhile, Atta, al Shehhi, and Jarrah had established an East Coast presence. All three arrived at Newark, al Shehhi first on May 27. Atta followed shortly, arriving on June 2. Jarrah arrived last, on June 27 and immediately flew on to Venice, Florida.

All three traveled abroad in early 2001, Jarrah to Beirut, Atta to Germany, and al Shehhi to Morocco. Both Atta and al Shehhi encountered difficulty upon return. Neither presented a student visa. Both persuaded Immigration and Naturalization Service screeners that they should be allowed reentry to continue flight training. Neither had any problem clearing customs.

The primary purpose of the advanced party was to obtain sufficient training and certification to pilot hijacked commercial airliners. Their main additional duty was to absorb enough cultural, language, and geographical expertise to pave the way for the arrival and care of the troops as they infiltrated. Not once did the six call enough attention to themselves to trigger a law enforcement intervention at any level—local, state, or federal.

With the advanced part well established, trained and mission ready, the next order of business was to infiltrate the troops deemed necessary for mission success.

Infiltration

Infiltration to the East Coast took place swiftly, from April to June, 2001, as depicted on the first slide. Part of that infiltration included the cross-county travel of al Hazmi and Hanjour, who had moved from Southern California to Tucson, Arizona. Hazmi and Hanjour arrived on the East Coast in early April 2001.

Mission requirement was for 15 additional troops to round out the crews. The effort was not quite successful. Thirteen individuals in five groups of two and one group of three infiltrated during the period late April to June 27, 2001. A fourteenth individual, al Mihdhar, himself an original member of the advanced party, completed the infiltration, symbolically, when he entered at Newark, New Jersey, on July 4, 2001. An alert immigration officer at Orlando, Florida, turned a fifteenth individual back on August 4, 2001.

There is scant, inferential content in the “SIGINT Retrospective” provided to the Congressional Joint Inquiry by the National Security Agency that suggests the al Mihdhar spent his final days abroad attempting to recruit one last individual. (This is based on my iterative reading of the Retrospective while on the Joint Inquiry staff.)

Once infiltration was complete the next task was one not included in the Power Point, mission-specific training.

Mission Training

We know few details about the extent of team training. The assumption is that such training was sufficient for the advanced party to decide who would be on what crews and what role each would play during the actual assault on the crews of the targeted airplanes.

At some point, a tactical decision was made that Ziad Jarrah would be short one team member. We can only speculate on why that decision was made. Atta and al Shehhi were focused on the main target, New York, and needed full teams. Hanjour had two of the advanced party with him, al Hazmi and al Mihdhar, and was the logical next choice for a full team. Those decisions left Jarrah, demonstrably the weakest link, holding the short straw.

Individually, all of the so-called “muscle” hijackers maintained physical fitness and picked up enough social and language skills to operate undetected in an unfamiliar society. Two were selected to participate in the most important training event, an orientation flight.

The military term of art is “terrain walk.” one method of preparing commanders and staffs for imminent battles by having them walk or at least observe the terrain on which they are going to fight. Altogether, six of the hijackers took part in that training, including all the pilots.

Orientation Flights

Orientation flights took place during the period late May (al Shehhi) to August (Hanjour and al Hazmi). Nawaf al Hazmi was Atta’s second in command, according to the Commission report, a logical reason for him to make an orientation flight. One additional attacker, Waleed al Shehri, took an orientation flight, alone.

Al Shehri was a member of Atta’s crew for AA 11 and his point of origin for his orientation flight (July 30) was Boston, as was Atta’s a month earlier. This may have simply been Atta making sure that at least one of his group had some sense of potential barriers to come. It could also simply have been validation and verification of cabin procedures after takeoff.

Assembly

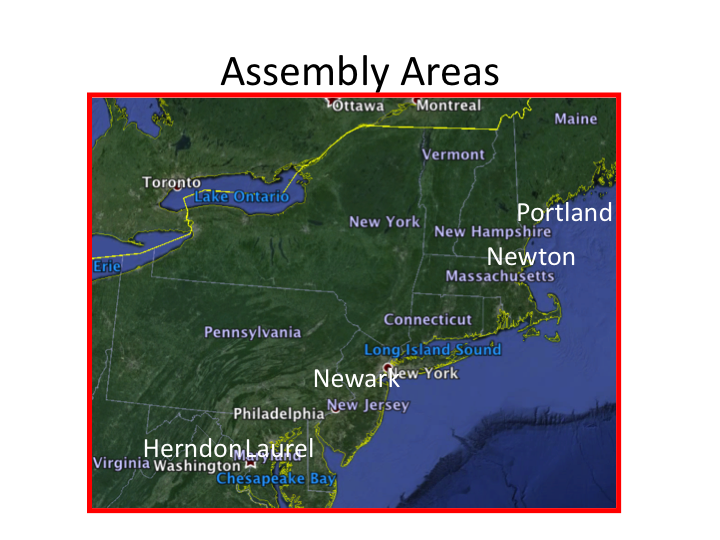

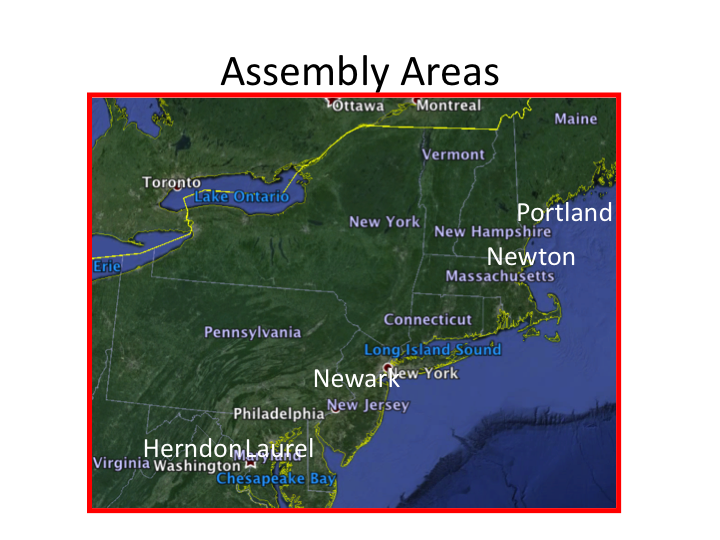

Once final plans were complete, training accomplished, and tickets purchased (August 25-September 5) the attackers moved quickly to assembly areas near their designated airports, with one exception.

AA11. Mohammed Atta and one colleague, al Omari, spent the night in Portland, Maine. The rest of Atta’s crew stayed in Newton, MA.

There is no contemporary information that explains why Atta chose Portland. Two explanations are logical using a military model. First, the Portland digression may have simply been to allow an early morning probe of the National Airspace System security posture at a small, local hub.

Second, it could have been a Plan B, an alternate scenario to allow Atta and one colleague to hijack one plane and fly it to a catastrophic end, given that all else had failed. That reduced accomplishment would still have been a success of sorts.

UA 175, AA 77, UA93. Al Shehhi and crew stayed at two different Boston hotels the night before the attack. The AA77 crew formed up in Laurel, Maryland and then stayed in Herndon, Virginia the night of September 10. The UA93 crew moved to Newark, New Jersey on September 7, and were joined by Ziad Jarrah on September 9.

The Final Hours. On the night of September 10, 2001, nineteen attackers in five small groups made their final preparations. They had passed through every layer of international, national, state, and local security with no alarm raised. Jarrah, himself, received an early morning speeding ticket in Maryland on September 9, with no consequence.

The attackers were not home free. Remaining ahead was passage into the National Airspace System. They had to cross the designated lines of departure.

Lines of Departure

Lines of departure are control features of any military attack to facilitate planning and execution. The attack on 9/11 had two such lines, an initial line of departure at Portland, Maine, and a final line of departure that extended the length of the north Atlantic seacoast from Washington DC on the south, through the New York metropolitan area, and on to Boston. Crossing of the lines was near flawless, with one potential misstep.

Portland. Atta and al Omari entered the National Airspace System at 5:45. The attack had begun. Atta’s expectation was that he and his colleague were safely through and would not face a further challenge in Boston. He had misjudged and become visibly angry when he learned he did not have a boarding pass for AA11 which required passing again through a security checkpoint. That was the potential misstep. According to the August 26, 2004, staff report:

The agent explained to Atta that he would have to check in with American Airlines in Boston…The agent remembers that Atta clenched his jaw and looked as though he was about to get angry…He said that Atta looked as if he were about to say something in anger but turned to leave.

The Final Line of Departure

Entrance into the National Airspace System was the single most critical aspect of the attack. Success hung in the balance. Retrospectively, we can assess that the planning was thorough and the execution swift and certain, as depicted in the following chart.

| Flight |

Scheduled |

Security |

Board |

Take Off |

| AA11 |

7:45 |

7:15+/- |

7:31-7:40 |

7:59 |

| UA175 |

8:00 |

7:15+/- |

7:23-7:28 |

8:14 |

| AA77 |

8:10 |

7:18-7:36 |

7:50-7:55 |

8:20 |

| UA93 |

8:00 |

7:30+/- |

7:39-7:48 |

8:42 |

Observations

The overall planned window of exposure (security, board, take off), excluding the Portland initial line of departure, was less than one hour (7:15-8:10). Including Portland, the window was two hours and twenty-five minutes (5:45-8:10).

Mohammed Atta (AA11) allowed al Shehhi and crew (UA175) to board and most likely enter the National Airspace System first, perhaps another probe to protect his own mission. Atta’s flight was scheduled to depart first and his crew boarded with just minutes to spare.

Based on available records, the first two attackers to enter the National Airspace System were Khalid al Mihdhar and Majed Moqed (AA77-Dulles). Both entered security screening at 7:18.

By any measure, the window of exposure was minimized. All attackers crossed the line of departure in less than 1/2 hour (7:15-7:36) at four widely dispersed entry points into the National Airspace System. Further, all then boarded within 32 minutes (7:23-7:55) on four different commercial airplanes.

Entrance into the NAS and boarding was predicated on scheduled departure times. The attackers planned that all would be in the air within a narrow time frame, just 25 minutes (7:45-8:10), and out of the reach of law enforcement and intelligence agencies at every level.

All that remained was to commandeer the four flights and fly them to target. Defense then rested with the airline crews, the air traffic control system and, if requested, four active air defense fighters, two at Otis Air Force Base, MA, and two at Langley Air Force Base, VA. Assault was imminent.

Two Axes, Four Prongs

The Northern axis was narrowly defined, a single departure airport, and the two-pronged attack unfolded with military precision. The Southern axis was broadly defined, two departure airports, and that two-pronged attack failed on one prong.

Takeover of the planes was swift, the crew and pilots were overwhelmed with simple weapons and physical force.

Dominance of the National Airspace System was achieved through tactical manipulation of the transponders. The following table depicts the timing of the attack as we know it, retrospectively.

| Plane |

Hijacked |

Transponder |

Impact |

| AA11 |

8:15+/- |

8:21 Off |

8:46-47 |

| UA175 |

8:43+/- |

8:46 Changed |

9:03 |

| AA77 |

8:53+/- |

8:56 Off |

9:37-38 |

| UA93 |

9:28 |

9:41 Off |

10:03 |

Author’s Note. Precise impact times are not relevant to this discussion and I have rounded them. Commission Staff preference was to use times rounded to the minute, but that became problematic concerning the impacts of AA11 and AA77. Ultimately, times as established by the National Traffic Safety Board were used in the final report.

The Northern Attack

The selection of Boston as a departure point for both planes had major tactical advantages. First, targeting two planes within a short departure window eliminated a key variable, departure time delay. Second, the narrow flight corridor for west-bound traffic was reasonable assurance that both AA11 and UA175 would be on the same frequency at the same time. Third, the selection of a United flight for the second plane provided an opportunity for Al Shehhi as a passenger on UA175 to listen to cockpit air traffic control communications on cabin channel 9. That was not a given, but likely.

First Prong. Atta commanded the flight efficiently and effectively. He turned the transponder off before turning south and while still in Boston Center air traffic control space. The sharp turn south in New York Center air space allowed a straight approach on a clear day to a highly visible target. If necessary he also had the Hudson River corridor to follow.

Second Prong. Al Shehhi’s command was equally efficient and effective. Whether or not he heard Atta’s broadcasts on frequency the evidence suggests he heard the UA175 pilot check in with the New York Air Traffic Control Center. Shortly thereafter the plane was commandeered. This had the net tactical result of presenting two different air traffic control situations to two different traffic control centers.

Although AA11 was in New York Center airspace the plane and its flight plan still belonged to Boston Center. There was no formal hand-off from one center to the other. As one result, it was Boston Center not New York Center that asked the cockpit of UA175 to confirm an altitude of 29,000 feet for AA11, which the cockpit did.

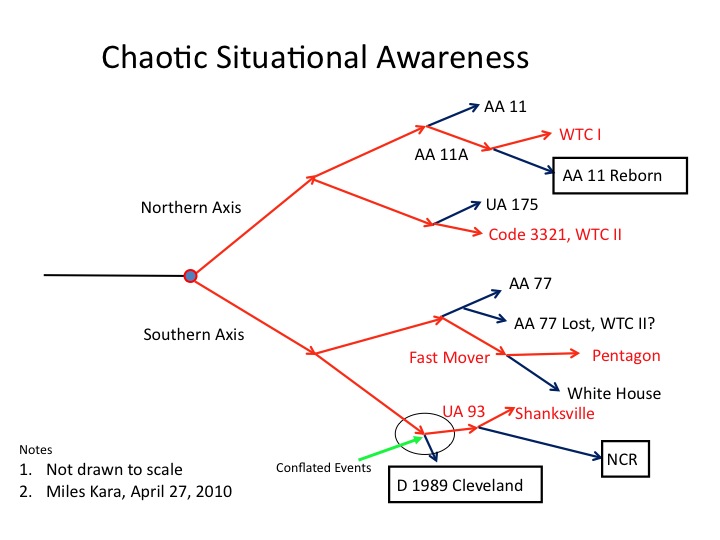

Because there was no hand-off, New York Center took initiative to enter a new track, AA11A, into the air traffic control system so that it could track the plane in its airspace. That was a reasonable action to take, but the net result was added complexity to a situation that was about to become significantly more confusing.

Chaos Begins

At precisely the time the fireball from the impact of AA11 became visible Al Shehhi changed the transponder code on UA175 to 3020. That had the tactical effect of introducing a Mode C Intruder into the air traffic control system. Such an intruder is a plane squawking a code not recognized by the system and it “intrudes” on controller scopes by presenting a track with no data block attached. New York Center, and the same controller at that center, now had multiple problems on their plate at the same time.

Al Shehhi flew leisurely over western Pennsylvania and northern New Jersey, well toward Trenton/Philadelphia. He made a second, unnecessary change to the transponder code (3321), made a high altitude, six-minute, 180-degree turn, and then plummeted his commandeered plane in a steep, high-speed dive directly into his target, which he had to bank to hit. The northern attack, a one-two punch with dramatic effect, was complete at 9:03.

That traumatized a nation and left New York Center and the air traffic control system with four known problems and one it did not know about. The known problems were: what hit the World Trade Center north tower? where was AA11? where was UA175? and, what was the Mode C intruder, code 3321, that hit the south tower? The unknown was what was happening to AA77 several hundred miles to the west.

The Southern Attack

The attack against Washington, DC, was likely planned to mirror the attack against New York City, one impact to gain media attention followed by a second impact. We do not know the sequence of attack or the designated target for each plane.

Nor do we know why the departure airports, Dulles and Newark, were selected. What we can assess, retrospectively, is that the plan required airliners that could be hijacked in the airspace of two different FAA en route control centers and not in Boston or New York Center airspace.

What we do know is that one target was the Pentagon and the other target was most likely the Capitol. I discount the White House as a target. It was too small, too obscure, and paled in comparison to the Capitol as either a target of choice or a target of opportunity.

Whatever the planned sequence for the southern attack, Hani Hanjour completed the mission of striking one of the two targets. Ziad Jarrah did not, for multiple reasons.

The First Prong

Intended or not, Hanjour struck first. The planning and coordination details remain obscure. Retrospectively, however, there is the appearance of detailed planning and coordination. The transponder on AA77 was turned off seven minutes after AA11 struck the World Trade Center, North Tower, and 10 minutes before UA175 struck the South Tower.

A simple plan, therefore, would have been to turn AA77 around prior to 9:00 and, concurrently, to turn off the transponder, regardless of what was happening to the North. The tactical actions of Atta and al Shehhi suggest that the southern attack was time-based.

Atta struck early, just fourteen minutes after takeoff, secured the cockpit, turned off the transponder and then turned sharply south and headed directly to target. Al Shehhi, on the other hand, took his time. He struck after UA175 crossed into New York Center airspace, waited for the fireball from the AA11 impact, immediately changed the transponder code, and then leisurely turned UA175 around. Once 9:00 arrived he plummeted steeply at high speed directly to target.

Based on that sequence of actions, my assessment is that AA77 likely was the first prong of the southern attack. I now assess that the timing of the turn back to target was time-based and not geography-based. That is a change in perspective. The unknown variable that morning was departure time delay. If Hanjour’s task was to commandeer and turn AA77 around in a given time-frame (9:45-10:00 8:45-9:00) then departure time delay did not matter, it was simply factored out of the equation. (Correction made Feb 17, 2015)

It was fortuitous, but perhaps not necessary, that the flight was commandeered in Indianapolis Center air space. The hijackers did not need to know the inherent radar issues at Indianapolis Center. It was sufficient to present a different problem—transponder turned off during the turn back to target—to a different Air Traffic Control Center. AA77 could just have well been hijacked in Washington Center airspace to meet Hanjour’s timeline.

Hanjour, in his approach to Washington, DC, followed the Interstate 66/Route 29 corridor. He descended from altitude to below 10,000 feet just south of Gainesville, Virginia. Ironically, at that time he passed nearly directly over Vint Hill Farms, the designated location for the new Potomac TRACON and, ultimately, the site of the new Air Traffic Control System Command Center.

Once Hanjour saw his target he executed a wide, descending, 330-degree turn to lose altitude, regain his target and then accelerate to impact. Hitting the Pentagon was the intent, but any impact short, left, or right would have been devastating. Coming up short, AA77 would have hit the Navy Annex. Crystal City was to the right. Rosslyn was to the left as was Arlington National Cemetery.

My seventh floor office at 400 Army Navy Drive, Crystal City, provided an unobstructed view of the Pentagon. I felt and heard the impact. By the time I got to the window, a matter of seconds, the fireball had dissipated and the sky was filled with black smoke and papers floating around at eye level.

We had no warning. At the time I and most colleagues were surfing the internet to follow events in New York City.

The Second Prong

Earlier we established that Ziad Jarrah had drawn the short straw, one that got even shorter as the morning progressed. The takeoff delay at Newark was 42 minutes, a good half hour longer than that experienced by any of the other three designated pilots. With just three colleagues he was still able to commandeer his targeted airliner, UA93. Whether or not cabin channel 9 was available on that flight, Jarrah and his crew did not strike until the flight was in Cleveland Center air space.

There is no clear picture of planned timing for UA93 as compared to the correlation of AA77 to AA11 and UA175. Given that UA93 was to be the second prong of the southern attack, the planning would have to correlate to AA77 and adhere to an overall plan to hijack four planes in the air space of four different Air Traffic Control Centers.

UA93 entered Cleveland Center air space at 9:24 and was hijacked within minutes. Jarrah had to wait 42 minutes (8:42-9:24) regardless of takeoff time.

UA93 was scheduled to depart 10 minutes prior to AA77. The departure delay that morning at Dulles (AA77) was 10 minutes. At Newark (UA93) it was 42 minutes. Assuming the plan was for the two departure delays to be comparable then UA93 was planned to be hijacked in the same time frame as AA77.

In other words, it was the planned intent that both planes in the southern attack be hijacked after the impact of AA11 and before the impact of UA175. Jarrah met just one of his two takeover objectives. He waited until the plane was in Cleveland Center air space. However, he had lost control of the timing.

Nevertheless, Jarrah managed to stay just inside the decision cycle of the defense. UA93 did take off before a New York Center ground stop was issued. His crew took over the cockpit as air traffic controllers were attempting to issue cockpit warnings to pilots. Air Force air defenders were poorly positioned. The Otis fighters were over New York City well to the north and the Langley fighters were two minutes from take off far to the South.

Even with those advantages Jarrah was fighting a losing battle. First, he had difficulty controlling the plane. On the turn back to target he could not maintain level flight and ascended to over 40,000 feet. Thereafter, he failed to maintain altitude but did manage to turn the transponder off. Worse, in the cabin, his colleagues were not able to prevent the remaining air crew and passengers from learning enough about events of the morning to take matters into their own hands.

With no help from any level of government, solely on their own recognizance, passengers and crew forced UA93 to crash, far short of the intended target. By 10:03 the battle was over, at least for the attackers. Not so for the defense.

The Defense

Concerning the Northern Attack, crews of two planes had been overwhelmed, their planes commandeered and flown to catastrophic fate.The Federal Aviation Administration knew it had a problem, but had no idea of what else was to come. An active air defense had finally been mounted, but solely in response to events in New York.

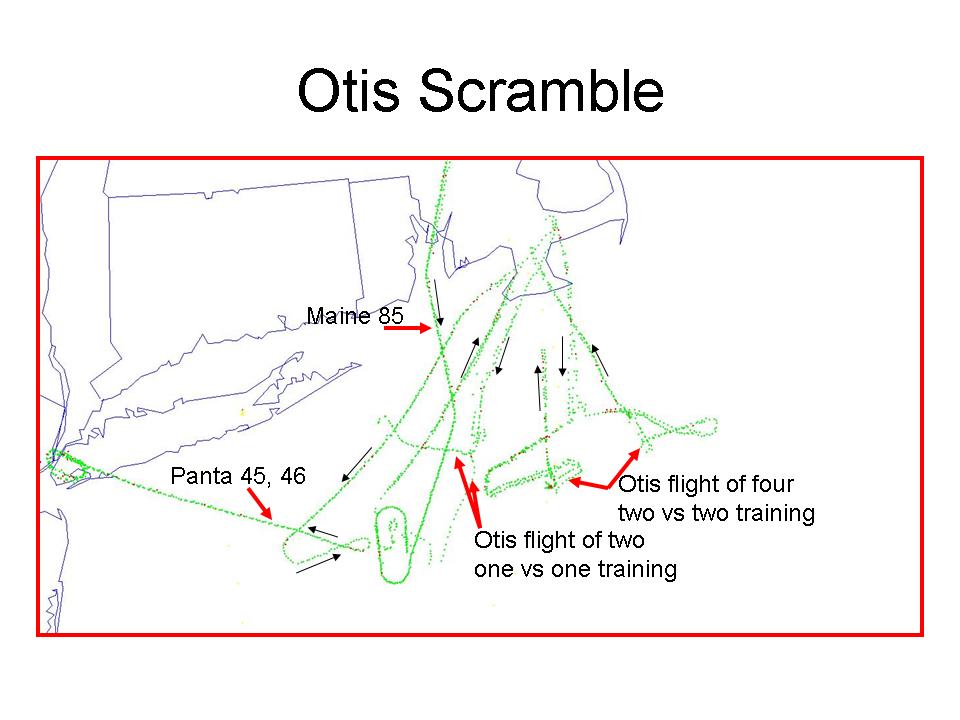

The Otis fighters were placed on battle stations at 8:40, scrambled at 8:46, and airborne at 8:52, an elapsed time of 12 minutes from the time the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) obtained actionable information from Boston Center, an outdated set of coordinates. That was a reasonable response, accelerated a bit because the Otis pilots had heard Boston Center’s initial call to Cape TRACON and, in effect, put themselves on battle stations before the order came to do so.

Shortly after the Otis fighters were airborne their controllers learned that they no longer had a target, a fact the pilots also knew, according to air traffic control communications. NEADS, the controlling organization made the tactical decision to continue and to put the fighters in a holding orbit in a military training area south of Long Island.

The fighters reached their western most point about 9:10 and began a holding pattern. That was, retrospectively, the single critical time for the defense.

The defenders had that single, fleeting moment of opportunity to better defend the nation’s capital. However, that is only known through retrospective analysis. No one, at the time, knew what else was happening. The one clue was that AA 77 had gone missing. That clue, unrecognized as another hijacking, was only known by Indianapolis Center. The Center decided that the plane was lost and initiated rescue operations.

The Southern Attack on the nation’s capital had begun, unrecognized. The attackers were still well within the decision cycle of their opponent.

9:10 EDT, A Critical Time, Retrospectively

At 9:10, the Otis fighters were at their closest point to Washington, DC, 225 nautical miles. The Langley fighters were on the ground in the Norfolk, Virginia area, 115 nautical miles to the south. AA77 was eastbound over central West Virginia, 48 nautical miles east of Charleston, WV, and 80 nautical miles west of Harrisonburg, VA. UA93 was westbound over Central Pennsylvania, just northwest of State College, PA.

In military terms, here is the disposition of friendly and enemy forces at 9:10:

At 9:10, Indianapolis En Route Traffic Control Center concluded that AA77 was lost and it initiated rescue procedures by notifying its higher headquarters, Great Lakes Region. Concurrently, the Center notified the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center.

At 9:10, the joint surveillance radar system supporting NEADS reacquired AA77 as a primary only, search target. NEADS surveillance technicians and identification technicians know what to do with primary targets. Finding, identifying, and tracking them is their bread and butter. No one told them to look to the West. Instead, they were concentrating on the skies over New York City and Boston.

At 9:10, NEADS considered engaging its remaining two air defense aircraft, the fighters at Langley Air Force Base. The NEADS Mission Crew Commander recommended the fighters be scrambled. The Battle Cab directed otherwise and the last remaining air defense fighters in the inventory were placed on battle stations. That was a reasonable decision at the time, given the information available. Retrospectively, it was exactly the wrong decision.

The Otis fighters were 25 minutes flying time away from the Pentagon. The Langley fighters were 13 minutes flying time away, but were still on the ground. The Otis fighters were airborne in 12 minutes from the call to battle stations (8:40-8:52). Applying that same standard to the Langley fighters they were also 25 minutes away. If tasked, in a perfect world, either set of fighters would have reached the Pentagon at about 9:35. (Flight times are based on a rate of progression of .9 Mach, as established by NORAD in its September 18, 2001, published timeline, explanatory note ****.)

9:10 EDT was the single, most important opportunity for the defenders to protect the nation’s capital. No one, at any level, had any idea of the disposition of enemy forces. Even worse, as events progressed, no one at any level had a coherent picture of the disposition of friendly forces. And that begs a question, Why Not?

Why Not

First the attack on September 11, 2001 was an attack against the National Airspace System. That precisely defined system had a single, named operator and a single, named defender on the East Coast.

The operator was the National Operations Manger (NOM), Benedict Sliney and his supporting organization the FAA’s Air Traffic Control System Command Center. The defender was the Commander, Northeast Air Defense Sector, Air Force Colonel Robert Marr and his supporting organization, the Sector Operations Center.

Sliney, in his first day on the job, and his predecessor had never met Marr. The two organizations had never interfaced in any meaningful way. Despite multiple exercises that suggested otherwise over the years, the two organizations had no procedures in place to rapidly share information or to handle hijackings. They did not share and had no way of sharing a common operating picture of the battlefield.

Second, the hijack protocol was not just out of date, it was obsolete. But no one knew that because if it had been exercised at all it was done so notionally. For example, the tapes from NEADS show that the exercise cell at NEADS played the roll of all higher headquarters in the ongoing exercise in the Vigilant Guardian series.

Third, not one national level mechanism for sharing information had yet been convened. The earliest convention was at 9:16, a NOIWON, a watch officer informal information exchange network. It was convened by the CIA watch center simply to try and find out what was going on. Ironically, the key voices (FAA, NMCC) were on the NOIWON call, but no one recognized that. (The 9:16 time is derived from documents released by NSA in reponse to a FOIA request for CRITIC messages of the day.)

FAA convened its primary net at 9:20, which included a link to the National Military Command Center (NMCC). That net never became operational and was subsumed into the FAA’s internal tactical net. The NMCC, at its end, convened a Significant Events Conference shortly thereafter. FAA could not be linked and the conference was terminated in favor of an Air Threat Conference at about the time the Pentagon was struck. FAA could not join that conference, either.

At the White House, the Secure Video Conference System (SVTS) was activated at 9:25. Richard Clarke convened a meeting of senior officials shortly after 9:40. Logs of the day show that Jane Garvey, FAA Administrator, and George Tenet, Director of Central Intelligence, entered at that time.

Also at the White House, the PEOC (President’s Emergency Operations Center) became operational at about the time the Pentagon was struck. The Vice President arrived shortly before 10:00 according to the 9/11 Commission Report.

National Command Authority

United 93 plunged to earth at 10:03. The battle was over and the National Command Authority (NCA) was just getting itself organized. The fate of UA93, known to Cleveland Center, the Air Traffic Control System Command Center, and FAA Headquarters, did not register at the Pentagon or the White House. The NCA diligently followed what it thought was UA93 because that is what they gleaned from TSD (Traffic System Display) information.

I established earlier that the simple tactical plan was to present four different situations to four different Air Traffic Control Centers using transponders as the weapon. There was no need for the attackers to know or even anticipate what would happen. It was sufficient to just create four different situations. Each Center reacted differently to the situation presented.

Boston Center could not hand off AA11 to New York Center. New York Center left the flight plans for both AA11 and UA175 in the TSD system and created a new track for AA11, AA11A. Indianapolis Center concluded that AA77 was down and initiated rescue coordination procedures. Cleveland Center was more creative and that became a problem no one anticipated.

Cleveland Center was tracking UA93 and knew it would enter Washington Center airspace if it continued on course. The Center, therefore, took the logical step, it entered a new flight plan for UA93 into the TSD system. That flight plan terminated at 10:28 when UA93 “landed,” notionally, at Reagan National Airport.

And that is the “plane” that Norman Minetta in the PEOC was following. His testimony to the Commission was one hour off. The time was 10:20, not 9:20 as he stated. National level awareness and understanding remained confused and conflicted thereafter.

Why? A fatal flaw in the NORAD timeline of September 18, 2001, established that the military was notified about AA77 at 9:25. That time was etched in stone in October, 2001, when General Ralph Eberhart testified to that time in an appearance before the Senate Armed Services Committee. Thereafter, the administration struggled to establish a narrative that the national level was responsive to the approach of both AA77 and UA93.

The narrative was doomed from the start. No one at any level vetted the work of staff officers at NEADS who made the initial error. Moreover, when NORAD and FAA prepared themselves for May, 2003, testimony to the Commission, no one at any level in either organization validated and verified the original NEADS staff work. The testimony of both Jane Garvey, FAA Administrator, and Norman Minetta, Transportation Secretary, conflated information concerning UA93 to correlate to AA77. NORAD representatives who followed did no better in their testimony.

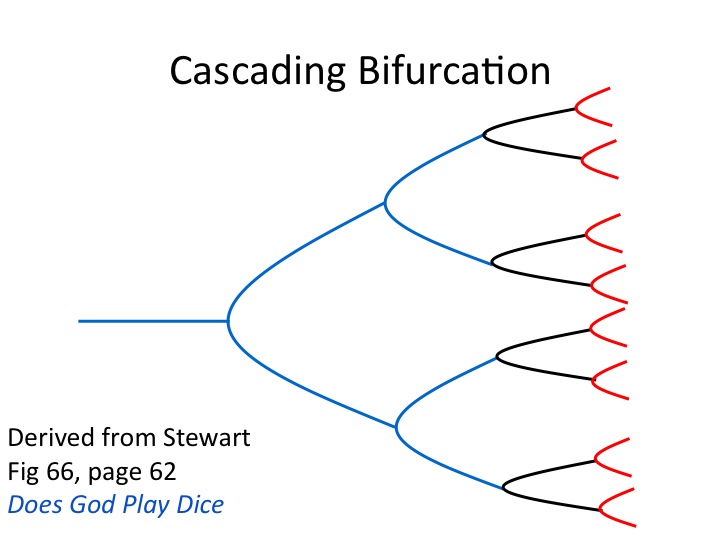

So, how did the national level get it wrong? The answer, in part, is in the language of chaos theory. And that discussion will be the third and final article in this series.

In the telling we will also look at why the Otis fighters were not available for the defense of the nation’s capital. Whatever else we might observe about their tactical maneuvering that morning they clearly disregarded the advice of Wayne Gretzky.

I skate to where the puck is going to be, not to where it has been.