D R A F T (This article needs some fine tuning)

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to document for the record the air traffic control communications at the Reagan National TRACON (DCA) concerning the Andrews fighters. The positions are F2, Final Radar, archived tape as provided to the Commission by FAA is “1 DCA 101-102 Tape 1-2 F2 1327 – 1450 UTC,” and Krant, Departure Control, archived tape as provided to the Commission by FAAis “1 DCA 99 Krant 1430-1600 UTC.” This article stands alone, narrowly focused on the FAA air traffic control positions most involved with the Andrews fighters. I will designate Krant communications as “Krant.” All other DCA communications are from the F2 position.

I am creating this article as backup for my presentation. “9/11: It Was ‘Chaos Out There,” to be presented on November 17, 2011, at the Air Force Historical Foundation and Air Force Historical Studies Office 2011 Biennial Symposium, “Air Power and Global Operations, 9/11 and Beyond.”

I am on the first panel, “9/11 and Operation Noble Eagle,” along with Maj. Gen Larry K. Arnold, USAF (Ret) and John J. Farmer, Jr., Dean, Rutgers School of Law, Newark.” Here is a link to the Symposium agenda.

We begin the Reagan National story with the first hint that change is in the air.

0950 – 1000

0952. DCA informed Patuxent (a military training area between Washington and Langley/Norfolk), “Do not let anybody in the Washington area. Tell ’em to go someplace and land.” 0952 Don’t let anybody in Washington area

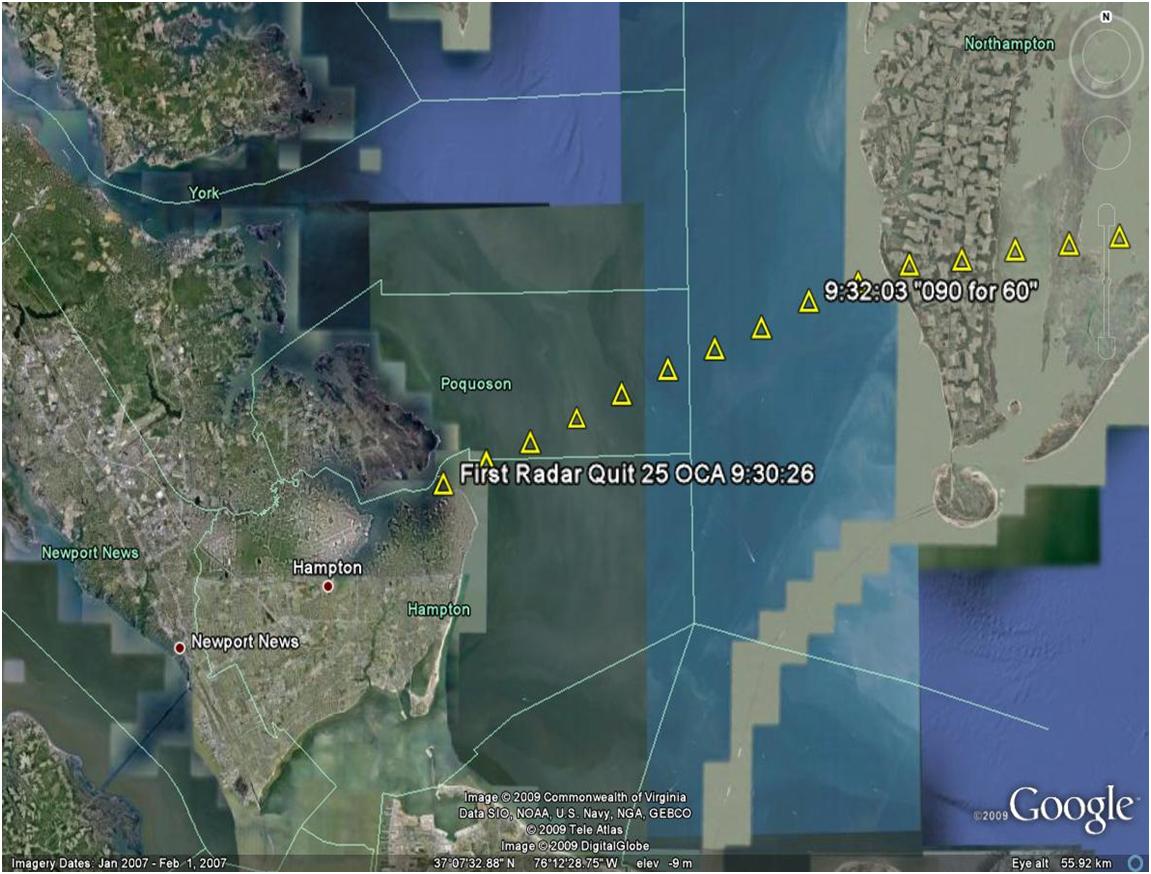

0957. The arrival of the Langley fighters came to the immediate attention of DCA TRACON. Even though the arriving planes were under the control of FAA’s Washington Center, DCA TRACON and other air traffic control facilities immediately recognized and acknowledged the presence of fighters in the area. In this next clip the DCA controller told a caller from Andrews Tower, “I don’t know who they are, but they’re somebody. Don’t worry about it, OK. They’re up high, they’re fighters.” The caller had asked if DCA knew who “those three emergencies” were, squawking about twenty thousand. The reference “emergencies,” refers to the fact that the Langley fighters were under AFIO, Authority For Intercept Operations, and were squawking 7777, the code for such operations. 0957 They’re up high they’re fighters

0959. DCA again told a caller do not land in his area. “They don’t want anybody in Washington airspace. 0959 No one in Washington air space

So what do me make of the activity at DCA?

My Assessment.

Earlier, at about 0934 when the alarm about the fast moving unknown (AA 77) was sounded, DCA TRACON established an open line with the Secret Service. It can, therefore, be assumed that when the DCA uses the pronoun”they” in this context the reference is to the Secret Service. These three communications, taken together, have to do with Presidential movement, the flight of Air Force One to the nation’s capital. Air Force One took off in Florida at 0955 EDT and headed directed toward Washington D. C. until 1010, at which time it turned west and headed for Louisiana.

This primary source information provides a glimpse into the advanced preparations for the arrival of Air Force One. Those preparations translated into a general shootdown order as a protective measure, not one issued in response to a specific aircraft. The Secret Service reports and actions will get more interesting as we examine the next time frame.

1000-1010

The first of the Andrews fighters returning from the range at Dare, North Carolina showed up in air traffic control channels. Concurrently, several things happened involving the Secret Service. At 1003 it provided an erroneous report that a Northwest airline was inbound to Washington D.C. from Pittsburg and was unaccounted for. That was probably a garble, more likely a reference to UA 93 approaching from the Northwest. Here is that report as recorded at Herndon Center on phone line 4530. 1003 SService reports NW airliner headed to DC

Shortly thereafter, at 1004, the Service directed a periodic broadcast from Andrews Tower announcing that Class B airspace was currently closed. All aircraft were advised to avoid Class B airspace. Any intrusion would result in a shootdown. 1004 Class B airspace closed

Class B airspace can extend as high as 18,000 feet, but the ceiling is generally lower. Class B airspace is the domain of the TRACON, in this case Reagan National. Because of the direct link between DCA and the Secret Service the order pertained strictly to the nation’s capital and only to that airspace under local control. Andrews Tower was an additional tower in the Reagan National controlled area.

Concurrently, DCA passed the alert to Herndon Center. Herndon, in turn, passed the warning to Washington Center (ZDC). 100442 DCA passes Secret Service warning

And, in the same time frame, Herndon Center learned that major Washington D.C. buildings were being evacuated, including the Capitol and the White House. 100224 White House Capital being evacuated

Bully Two showed up in the middle of all that activity. DCA had just passed the Secret Service alert to BWI TRACON and was told by Swan position, Washington Center, about a hand off. DCA told Swan to turn the plane around, but quickly changed that order when the DCA controller learned that it was Bully Two. 10004 Bully Two returns

Here is the series of clips concerning Bully Two from a DCA perspective. The critical information needed was whether or not he was armed and, if not, could he be armed at Andrews. To expedite Bully Two’s approach DCA cleared him direct to Andrews.

1006 Are you armed 1007 Can you be armed 1008 Bully Two unable for fuel

It is clear from this sequence that the DCA controller was communicating with the Secret Service and was relaying questions. We can surmise that the plan was to use Bully Two, in some fashion, as an asset in the air. This, despite the fact that the Langley fighters had already established a CAP over the nation’s capital and were available, as was known to FAA controllers and was surely known to the Secret Service.

The first plan for Bully Two was to keep him in the air. When he reported he was not armed the plan changed to land him, get him armed, and then back in the air. That plan included a check on his fuel status.

Despite that flurry of activity, Bully Two was not relaunched. Commission Staff was told that he was a new pilot and that the Wing waited for Bully One and Bully Three to return.

At 1010. the situation was that Bully One had returned and was available. The Langley fighters had established a West-East CAP at 23,000 feet. The E4B, Venus 77, was establishing a North-South, 60-mile leg orbit centered on Richmond, Virginia. Bully One and Bully Three were en route North from Dare Range, North Carolina. At 1010, Air Force One turned away from its approach to the nation’s capital and turned West.

1010-1020

We learned in the Nasypany articles [link is to Part V] that the situation quieted down at NEADS during this time. UA 93 and D 1989 had been accounted for and there was nothing on the horizon, air defense-wise. The battle was over.

That quiet interlude was mirrored at DCA. The only thing of note during a nearly ten minute period was DCA learning that tanker support for the Langley fighters had arrived. Washington Center, Swan Center, reported “tankers at nineteen seven [19,700 feet].” 1016 Tankers at nineteen seven

The quiet was interrupted by the return of Bully One. DCA told the caller to “bring him home.” The flight plan said the flight of two was landing at Patuxent. That was changed and DCA was told “he will be coming to you.” 1019 Bully One flight of two F-16s

In summation, as of 1020 the air defense battle was over. Bully Two had recovered to Andrews and Bully One, flight of two, was approaching the nation’s capital. Activity would again pick up at DCA as it dealt with the emerging Andrews situation.

1020-1030

At 1022 a called asked if DCA was aware of a hijacked aircraft in the area. DCA responded that it was. The called asked where it was. DCA responded, “we don’t know exactly.” The caller responded, “is he coming from the West?” Answer: “Yes.” 1022 You aware of a hijacked aircraft

At this time it was still not known what aircraft hit the Pentagon and this could be a reference to either AA 77 or UA 93.

At 1023 Dulles reported a helicopter, a medivac out of Hagerstown, that wanted to return to Davison [Fort Belvoir]. DCA strongly advised against the return, “he will be shot down.” 1023 Medivac Hagerstown to Davison Hagerstown was the point of origin of the revised flight plan for United 93 as filed by Cleveland Center.

At 1027, Bully One was cleared direct to Andrews. 1027 Bully One cleared direct Andrews

At 1028, DCA learned that United 93 was no longer being shown in the system. This is a reference to the flight plan system and to the associated traffic situation display. The flight plan entered earlier by Cleveland Center terminated the flight at Reagan National at 1028. That termination was recognized immediately by someone in the FAA system and reported in near-real time to DCA. United 93, which crashed at 1003, ceased to exist, even notionally, before Bully One landed. 1028 United 93 no longer in the system

At 1029, DCA asked Swan if he was talking to Quit 25. He was. DCA said he would get back to him, he thought Secret Service might have a question for him. It is clear from this exchange, as heard in real time, that DCA was talking to the Secret Service. 1029 Are you talking to Quit 25

As of 1030, there was no known threat, real or notionally. United 93 was not an issue. A helicopter was attempting to return to Davison Air Field from Hagerstown, as reported by Dulles TRACON. Bully One, flight of two, was cleared to land. The Secret Service knew that the Langley fighters were in the area. DCA was standing by to relay questions to the Langley flight lead, Quit 25, via Swan.

There was no apparent need to launch Andrews fighters, yet they were sortied, as we shall learn.

1030-1040

First, at 1030, DCA relayed a message to Krant to have the Langley lead, Quit 25, change frequency so he could talk to Reagan National directly. 1030 Have Quit 25 change frequency

Within a minute, Quit 25 was talking directly to DCA. He was told, “Secret Service wanted you on this frequency.” Quit 25 said, “go ahead” and was then told to “stand by a second.” 1031 Secret Service wanted you on this frequency

For the next minute, DCA was off microphone most likely talking to the Secret Service. The DCA controller then came back to Quit 25 at 1032 and in a nearly two minute conversation verified four things. First, he confirmed that the fast movers at altitude 240 and 250 were with Quit 25. Quit 25 confirmed that they were his number two and number three wingmen. Second, he confirmed that there was no traffic in the Washington area. In other words, no targets. Third, he confirmed that fast movers to the east were part of the operation. Quit 25 confirmed that they were his refueling aircraft. Finally, he confirmed that the military had control of the airspace and that DCA would simply act as a relay. 1032 The air picture established by DCA and Quit 25

At this point we lose the Bully One story as he switched to Andrews Tower frequency. I will come back to that later, but let me summarize here. At first, Bully One was told to proceed to E ramp to get armed. At about 1036 those directions were coutermanded and Bully One reported that he had orders from his commanding general to get back in the air. We will pick him up again when he switches back to a DCA frequency.

At 1033 Krant advised Swan of some primary targets northwest of Washington and asked that the information be passed to the Langley fighters. Krant confirmed that he was talking to Quit 25. Krant also learned that military aircraft could return to base. Specifically, the medevac helicopter from Hagerstown had permission to return to Fort Belvoir. 1033 Krant military aircraft can return to base

Meanwhile, Quit 25 addressed an unresolved issue with DCA. NEADS had been under the impression for some time that a “First, flight of four” from Langley were in the air as part of the support package for the return of Air Force One. That information had been passed to Quit 25 and he asked DCA about it at 1036, the same time as Bully One was receiving orders to get back in the air. DCA confirmed with Washington Center that there was no “First, flight of four” from Langley. 1036 No First flight from Langley

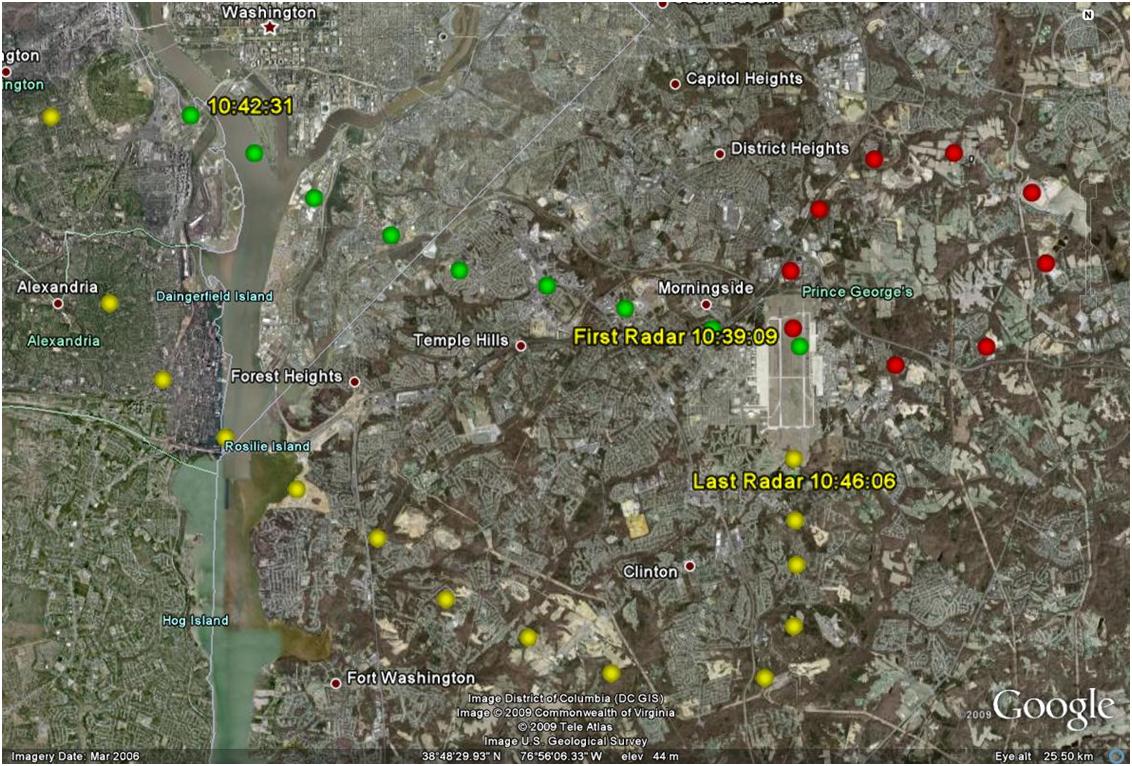

At 1038, Krant position, Bully One’s departure for radar intercept was announced. 1038 Krant Bully One departure for radar intercept

During the next two minutes, DCA talked primarily to Quit 27, the first time we hear his voice. DCA confirmed the CAP configuration (East-West) and the identity in the air of each of the three Langley fighters. He also learned that Quit 26 was in direct contact with Huntress (NEADS). At 1040, Quit 25 was advised that an F16 ([Bully One] had just departed Andrews. 1038 CAP discussed 1040 F16 just departed Andrews

At 1039, Bully One checked in with Krant and asked for instructions to check out an aircraft flying down the river. He was given instructions to check out what aircraft it was. He was told to head toward Georgetown. 1039 Krant Bully One checks in for instructions

As of 1040, DCA was communicating with Secret Service and was acting as a relay from the Service to the Langley lead, Quit 25. DCA knew the Langley CAP configuration and had identified each of the three aircraft in it. The DCA controller knew that the Langley flight was talking to Huntress [Quit 26]. He also confirmed that the Langley flight knew about its tanker support, to include location. Bully One had launched and was told to head toward Georgetown. Despite that air defense protection of the nation’s capital the first Andrews response, the relaunch of Bully One, heralded another chaotic event, the merger of the Langley and Andrews fighters into a coherent operation.

1040-1050

At 1040, the refinement of the Langley CAP and its control continued. Quit 25 advised DCA that the Langley flight would need to cycle through the tankers one at a time. That would require some coordination by DCA. The DCA controller was also advised that Huntress (NEADS) wanted to talk to him. A number was provided by Quit 27. Presumably, that number was then available to the Secret Service. 1040 Tanker support and give Huntress a call

At the same time, Bully One was told that the airspace belonged to the military for the operation [Huntress/Langley], that there were several helicopters in the area, and nothing else, right now. Bully One reaffirmed that he was sent aloft for a target. Krant responded, “that information probably came through your source, not ours.” Concurrently, in a comms over ride, the launch of the first pair of Andrews fighters, Caps flight, was announced. 1040 Info from your source not ours

Krant continued to work with Bully One at the same time that Caps one was checking in. 1041 Krant Bully One and Caps One

Concurrently, for several minutes, DCA continued to work with the Langley flight to coordinate squawks and tanker support. Quit 25 needed to split off and refuel. DCA informed Quit 27 that at the Huntress (NEADS) number provided, “whoever answered has no idea what we’re talking about.” DCA and Washington Center also discussed an unknown target, 3666, northwest of Manassas airport. 1041 Team 23 tanker support and target NW of Manassas 1042 Working out squawks with Quit flight 1043 Huntress number no idea

Also concurrently, a significant discussion took place between Caps One and Krant position. Caps One asked for a vector to an unknown, unidentified aircraft, inbound. Krant responded that there was no target, “as far as we know.” Caps One then asked if Krant was in contact with the National Command Authority. The response was explicit, “affii rmitive.” Thereafter, Caps One said they would orbit at whatever location Krant desired. The Caps flight was directed to establish an orbit about 10 miles to the Northwest of Washington at 11,000 feet. Caps One acknowledged, “eleven thousand would be fine.” 1042 Krant You in contact with NCA Affirmative

By 1043, Bully One confirmed that he had no targets and was headed back to Andrews. He was advised of the Caps flight presence and its location. Bully One’s status report to Krant was, “I have no other aircraft on my radar, and we only have helicopters out here, so I’m going to proceed back to Andrews.” 1043 Krant Bully One no other aircraft on radar

At 1044, Krant and Caps One discussed a possible target. Caps One was told about a possible unknown, helicopters over the Pentagon, Bully One returning to base, and F-16s at 250 “on top of you.” The conversation was predicated on Caps One asking for confirmation that he had no unknown civilian target as he was advised prior to takeoff. This is primary source confirmation that the Andrews fighters knew about the Langley fighters at altitude. 1044 Krant F16s above you

At 1047, Caps One persisted in his hunt for a target. He asked Krant, “are there any blind spots in your radar coverage.” He was told, “just, right over DCA.” 1047 Krant any radar blind spots

At 1048, Caps One was told that the Wild flight was five minutes away from launch. As Krant and Caps One sorted out the CAP configuration, Caps One made a significant statement concerning the Wild position. The Wild flight would be centered south of Andrews and that “would be at peace, as well.” That is the only statement of ROE (Rules of Engagement) status for the Andrews fighters of which I am currently aware in primary source information. 1048 Krant Wild at peace as well

Compare that status statement with a similar statement two minutes later by Major Fox, Senior Director, NEADS. Fox was asked about authority concerning a target in the Boston area. His answer was, “at peace.” 0911145222 Request Clearance to Shoot

Therefore, as of 1050 both NEADS and Andrews, separately, were operating under “at peace” ROE, despite Vice Presidential guidance to the contrary as recorded in the NEADS chat log shortly after 1030 1032 You need to read this

I am stopping this narrative for now. Remaining is the contentious arrival of Wild One on the scene and the struggle to establish a joint CAP between the Langley and Andrews fighters. Part of that story is the DEFCON status change promulgated by the Joint Chiefs of Staff at 1052.

To be continued