Introduction

This is the third and final in a series of articles dealing in military terms with the events of September 11, 2001, and the aftermath. The first article dealt specifically with the classic principles of war. The second article examined the components of the attack from a military point of view. We turn to chaos theory in this last article to better understand why the nation was confused as to what was happening and why it remained confused, thereafter.

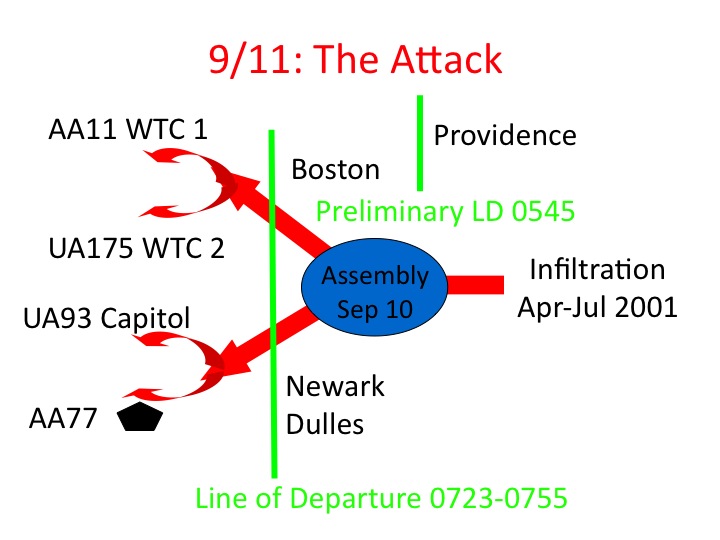

In the second article we established that the attack was on two axes, each with two prongs. That is a complex operation, irrespective of scale. Such an attack is intended to create chaos and confuse the opponent.

The descriptive, “chaos,” is routinely used by authors to describe the events of 9/11. The Commission report is no exception. No author or commentator bothers to define chaos, it is simply used as shared knowledge between author and reader. Here are links to earlier articles that provide some insight.

Chaos Theory and 9-11, some preliminary thoughts

Chaos Theory: 9-11, thinking outloud

Chaos Theory: the butterfly effect, a ghostly experience

Chaos Theory: Unbuilding the World Trade Center, dealing with Chaos

Chaos Theory, Considered

We begin with a brief discussion about the definition of chaos. Here are three useful perspectives, to set the stage:

- Merriam-Webster: Complete confusion and disorder: a state in which behavior and events are not controlled by anything

- Bartlett’s Quotations: Chaos often breeds life when order breeds habit (Credited to Henry Adams, The Life of Henry Adams)

- Lewis and Carroll, Humpty Dumpty: A portmanteau word, one packed with meaning

The dictionary definition is the sense that most people have when they refer to something as chaos or chaotic. And that is the shared, knowing understanding between authors and readers about the events of 9/11.

The Barlett Quotation contrasts what chaos is all about with what we do to get through day-to-day life. We instill order–habits for ourselves, and routines for our families and social groups. For the defenders on 9/11, the order was standard operating procedures or tactics, techniques and procedures, routines that were supposed to work. Even though chaos lurks daily at every turn, we hope that processes and procedures in place will stand us in good stead.

M. J. Girardot, in writing about early Taoism, (Myth and Meaning in Early Taoism) decided that the Chinese word for chaos, hun-tun, was, from Lewis and Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty, a portmanteau word, that is one packed with meaning. To Humpty, chortle was chuckle and snort packed together. To us, avionics, aviation and electronics, is a portmanteau word.

Regardless of definition or perspective, chaos is deterministic. Chaos has bounds and can be described using mathematics, the logistic equation and fractal geometry, for example. However, the mathematics of chaos cannot be applied to the events of 9/11, despite the near universal use of the word to describe what was happening and what did happen.

There is a possible exception. It is conceivable that fractal geometry could be used to map the progress of the massive cloud of dust and debris that resulted from the collapse of the two towers. If so, some future mathematician will create the map.

Mathematics aside, what we can do is use chaos as a metaphor. Specifically, the language of chaos provides a useful qualitative tool for assessing what happened during the battle, in the immediate aftermath, and thereafter, to this day.

The Language of Chaos

Four terms help us “unpack” the portmanteau of chaos concerning the Battle of 9/11.

- Strange Attractors

- Nonlinearity

- Cascading Bifurcation

- Disruptive Feedback

However, there is a fifth, overarching term that we need to discuss first, sensitive dependence on initial conditions, commonly referred to as ‘the butterfly effect.’

The Butterfly Effect and 9/11

Dependent initial conditions are only knowable retrospectively. I leave it to the long reach of history to provide a refined list of initial conditions important to the events of September 11, 2001. Two candidate topics come immediately to mind; the ‘wall’ between law enforcement and intelligence, and the relaxed visa issuance process in Saudi Arabia that would become Visa Express.

Concerning the Battle of 9/11, two initial conditions stand out, the hijack protocol, and the lack of a defined relationship between the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) and the Federal Aviation Administration’s Air Traffic Control System Command Center (Herndon Center).

The hijack protocol was obsolete. It had not been used for years and if exercised at all the exercise play was notional. Herndon Center did facilitate a conference call with Cleveland and New York Centers and then with New York TRACON when Boston Center notified Herndon about the hijacking of Americsn Airlines Flight 11 (AA 11). However, Herndon Center simply referred the requirement to notify air defense back to Boston Center.

NEADS, the controlling organization for the four dedicated air defense aircraft, had a long established practice of dealing directly with the en route traffic control centers, specifically Boston and New York. At no time during the battle of 9/11 did NEADS ever talk to Herndon Center. NEADS simply got on with business as if Herndon Center did not exist. It is not surprising, in retrospect, that NEADS and Boston Center became “strange attractors” in the language of chaos theory.

Strange Attractors

Ian Stewart in Does God Play Dice, has it about right. “A…dynamical system…in the long run, settles down to an attractor…defined to be…what ever it settles down to.” The concept is that strange attractors cannot be predicted. Things self organize and information flows to and between specific, receptive entities.

Managers and leaders can only strive to organize things in the hopes they might get lucky in their vision of the future. Ideally, one would like the flow of information in a chaotic situation to be to the people or places that need it the most.

The fact of the matter is that information will follow the path of least resistance. If there are barriers in place, ‘The Wall,’ ‘The Green Door,’ A hijack protocol that was in the words of a Commission Team 8 memo to the front office, “unsuited in every respect” to the events that would occur, then there is no chance in a fast-moving chaotic situation.

In a very perfect world the defense on 9/11 might have had a remote chance, if and only if the strange attractors were the operator of the NAS and its defender on the East Coast. Those were named individuals, Benedict Sliney, the National Operations Manager, and Colonel Robert Marr, the commander of NEADS. They had never met, their predecessors had likely never met, and their organizations did not communicate with each other either in the real world or in exercises.

What ever it settles down to. Organizationally, the strange attractors became Boston Center and NEADS, but the identity of the strange attractors is far more precise than that. The flow of critical information was largely controlled by just two individuals, the Military Operations Specialist at Boston Center, Colin Scoggins, and the chief of the Identification Section at NEADS, Master Sergeant Maureen “Mo” Dooley.

That was a sub-optimum solution all around. Herndon Center and NEADS, separately, were talking to the front line of troops, the FAA’s en route air traffic control centers—New York, Washington, Indianapolis, Cleveland, and Boston. However, the two organizations never shared a common operating picture of the battlefield.

Government, by and large, operates in a linear world. In that world, NEADS focused outward and established tactics, techniques, and procedures to protect the nation’s shores. To do so it logically established working relationships with FAA en route centers that controlled overseas and off shore flights. For its part, Herndon Center focused inward to manage the flow of air traffic between en route centers. There was no logical reason for the twain to meet. So they didn’t.

The NEADS world was linear, punctuated by occasional bursts of chaos when unidentified tracks showed up on their scopes. The Herndon Center world was largely chaotic, by necessity. Its daily foe was weather, a chaotic creature by any definition. It is no accident that a key position at Herndon Center is called Severe Weather. To put it another way, the NEADS world was largely linear, the Herndon Center world was decidedly nonlinear.

Nonlinearity

Nonlinearity is another difficult term to define in terms of chaos theory. Most of us have had experience trying to hit a pitched baseball or softball. If nothing else that experience teaches that we live in a nonlinear world, despite what we might have learned in high school geometry.

For perspective, we turn again to Ian Stewart in Does God Play with Dice. “Linearity…to be brutal…solves the wrong equations.” “[One hopes] that no one will notice when it’s the wrong answer.” “Nature is relentlessly nonlinear. Linearity is a trap.”

And that’s the problem with linear processes or procedures. They provide the wrong answer in a dynamic situation. Yet, with minor exception, the nation’s response on 9/11 was linear. Here is a list of linear processes that solved the wrong equations leading to a series of wrong answers.

- Hijack Protocol

- FAA Primary Net

- National Military Command Center (NMCC) Conferences

- Secure Video Teleconference System (SVTS)

- Rescue Coordination Center

- Continuity of Government

Every process listed was attempted and failed during the battle of 9/11. Why? Each process brought with it the baggage of linearity—things were done by rote, by SOP, or by tactics, techniques and procedures.

The hijack protocol wasn’t even used. It failed when Herndon Center turned the responsibility to notify the military back to Boston Center.

The FAA primary net and the two NMCC conferences that were convened failed to connect the FAA and the military in any meaningful way.

The SVTS, a cold-war, isolated system, to put it bluntly, decapitated the leadership of national level organizations by separating them from their staffs.

The Rescue Coordination Center at Langley knew that American flight 77 (AA 77) was lost at 9:10. That information never made it to Base Operations, a party to the battle stations and scramble calls from NEADS to the air defense detachment at Langley.

The NMCC’s convention of an Air Threat Conference, at NORAD request, brought with it SIOP (Single Integrated Operations Plan) baggage and facilitated a rapid government decision to implement unnecessary Continuity of Government and Continuity of Operations procedures.

Accurate, controlled feedback was needed all along the line. Uncontrolled feedback becomes disruptive and that is what happened on 9/11. Once it was known Mohammed Atta said, “we have some planes,” and New York Center confirmed,”planes as in plural,” the situation became nonlinear. The nation had no dynamic response. Instead, linear procedures continued and the President and Vice President were summarily dispatched from the battlefield, one to PEOC (President’s Emergency Operations Center) purgatory, the other to hightail it to the hinterlands.

Boston Center and Herndon Center, two notable exceptions

Boston Center, left to its own devices, called Otis Command Post directly in an attempt to get air defense fighters involved. Even so, they ran squarely into linearity and were told that had to work through NEADS. Later, the Center appealed to Herndon Center to direct cockpit notifications to flights in the air. Boston did not wait for that direction and began calling flights in its air space directly.

Herndon Center, habitually conditioned to handle chaos because of weather, did not wait for guidance from above. Benedict Sliney directed a nationwide ground stop and then grounded all commercial flights in the air. Chaos is deterministic, it can be bounded. And Herndon Center did just that, it bounded a chaotic situation, just as it does every heavy weather day.

Those simple and swift decisions put a stop to cascading bifurcation, the next term on our discussion list.

Cascading Bifurcation

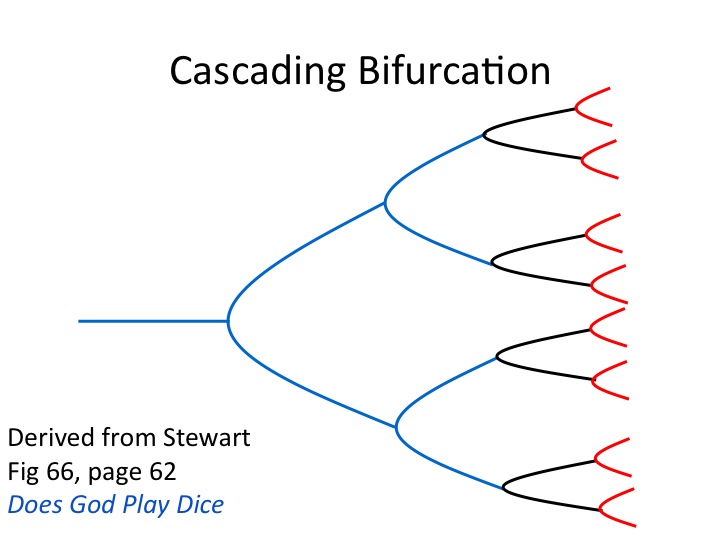

We don’t need a detailed discussion when a picture will do, derived from the work of Ian Stewart.

In a chaotic situation bifurcation continues until things self-organize differently than they were before. The first two bifurcations should be immediately recognizable. They represent an attack on two axes of advance, each axis with two prongs. For the offense the bifurcation stopped there. For the defense the bifurcation continued as false information, misinformation, and lack of information brought about chaos. And that chaos continued during the battle of 9/11 until Benedict Sliney brought things back to order, certainly much different than they were before. But not before disruptive feedback produced a discordant chorus of information that simply overwhelmed the national level.

Disruptive Feedback

For insight we turn, in this instance, to Jim Lesurf, Chaos on the Circuit Board, “New Scientist, June 1990.” According to Lesurf, “feedback must be added with care….Adding feedback to a nonlinear [situation] with gain is a recipe for chaos.” Here are the important examples of disruptive feedback that became ingredients for the 9/11 chaos recipe.

- A new track, AA 11 Alpha

- False report that AA 11 was still airborne

- Report that Delta Flight 1989 was hijacked

- A new flight plan for United Flight 93 (UA 93)

- Report of an unknown aircraft over the White House

New York Center added a new track because the standard procedure was that Boston Center had to ‘hand off’ AA 11, something it thought it could not do. The new track, combined with a late report that American Flight 77 was lost, may have contributed to erroneous information that AA 11 was still airborne. Delta 1989 was presumed hijacked because it fit the sketchy profile concerning AA 11 and United Flight 175 (UA 175). A sudden change in the flight plan for UA 93 created a track in the Traffic Display System (TSD) that became notional but was perceived as real. The “unknown” over the White House was one of the Langley fighters. In the ensuing chaos, one Langley Fighter was sent to intercept another. Two of the three Langley fighters were squawking identical codes and neither Washington Center nor NEADS could tell one from the other.

A Quick Summary

At this point the reader likely needs time to digest what we’ve covered so far. There are heavy seas ahead as we steer the narrative deeper into chaos by bringing cascading bifurcation back into the conversation. So before we do that, what have we learned? First, we have learned that the military model we discussed in the first two articles in this series continues to be useful. Second, we now have a grasp, however tenuous, on the use of chaos as a metaphor, specifically the language of chaos. Interested readers may want to devote time to Ian Stewart’s book, Does God Play Dice.

Okay, now that we’ve caught our breath let’s return to cascading bifurcation and see what effect the attack on two axes of advance, each axis with two prongs, had on the defense on the morning of September 11, 2001. We start with a timeline of the attack and the national response, a highly condensed but straightforward and expanded depiction of Chapter One of the Commission Report, “We Have Some Planes.”

The Attack, Retrospectively

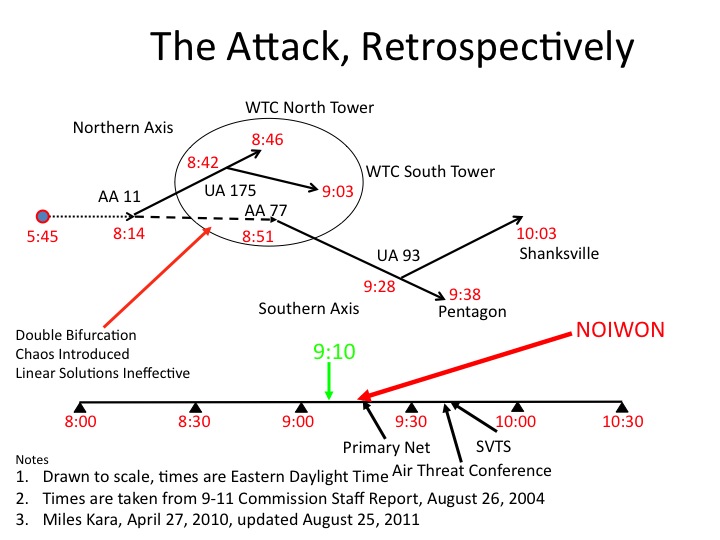

The base time line represents national level actions. A NOIWON was convened at 9:16, the FAA’s primary net was activated at 9:20, the NMCC’s air threat conference was activated about the time the Pentagon was struck. An SVTS conference was convened at 9:40. The critical 9:10 time, in green was nowhere recognized as an opportunity.

The progression of the attack is depicted above the timeline. Clearly, by the time the national level achieved some semblance of organization, the only plane left to deal with was UA 93. And it is on this very point that the national level account in the aftermath was incoherent. The account, which focused on AA 77, was fatally flawed from inception.

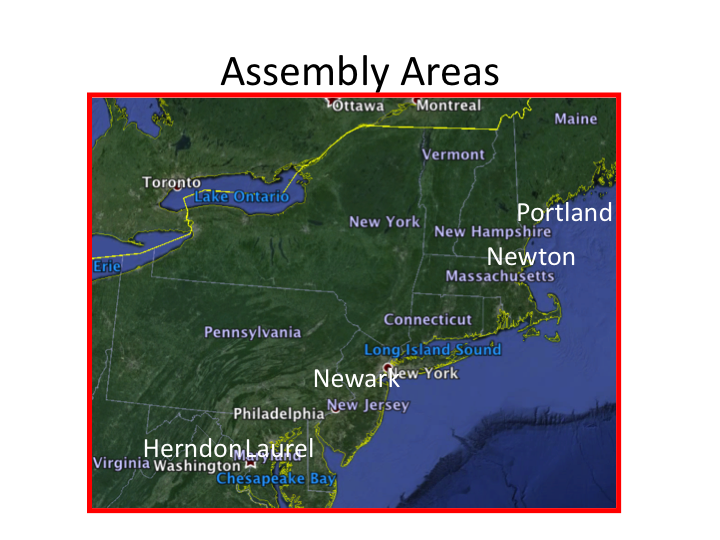

The attack began at 5:45 when Mohammed Atta and abdul Azziz al Omari entered the National Airspace System at Portland, Maine.

Chaos was introduced during the period 8:42 to 8:51, the approximate times that UA 175 and AA 77 were hijacked. Bifurcation had begun, but had not yet cascaded.

AA 11 was hijacked at 8:14 and crashed into the World Trade Center, North Tower, thirty-two minutes later, at 8:46. UA 175 was hijacked at 0842 and crashed into the south tower twenty-one minutes later at 0903. The Northern axis of the attack was over and the southern axis overlapped and was in progress.

AA77 was hijacked at 8:51 and slammed into the Pentagon forty-seven minutes later at 0938. The timing of the second prong of the southern axis was delayed by the late takeoff of UA 93 from Newark. That plane was not hijacked until 9:28 and plummeted to ground at Shanksville thirty-five minutes later.

From time of takeover of AA 11 to the demise of UA93, the attack lasted just one hour and forty-nine minutes. The most chaotic time was from 8:42 to 9:03. During that twenty-one minute period two planes were hijacked (UA 175 and AA 77) and two planes crashed into the World Trade Center (AA 11 and UA 175). It was a double bifurcation. The main attack bifurcated into two axes and the northern axis bifurcated into a two-pronged attack.

Dimly aware of the complexity of a single two-pronged attack, and unaware of the developing of a second axis of attack, the national level response was to activate cumbersome linear response systems. While UA 93 was being hijacked the nation was struggling to activate its three primary response processes, the FAA primary net, an NMCC conference of some sort, and an SVTS conference.

No one at the national level realized that all the key agencies were already communicating via secure phone. At 9:16 the CIA convened a NOIWON conference to try and find out what was going on. Every member of the WAOC (Washington Area Operations Centers) was on the line, including the FAA.

The net result of the persistence in following established procedures was that the nation’s leadership and crisis management system had no chance to take advantage of the single time at which actionable information became available, 9:10.

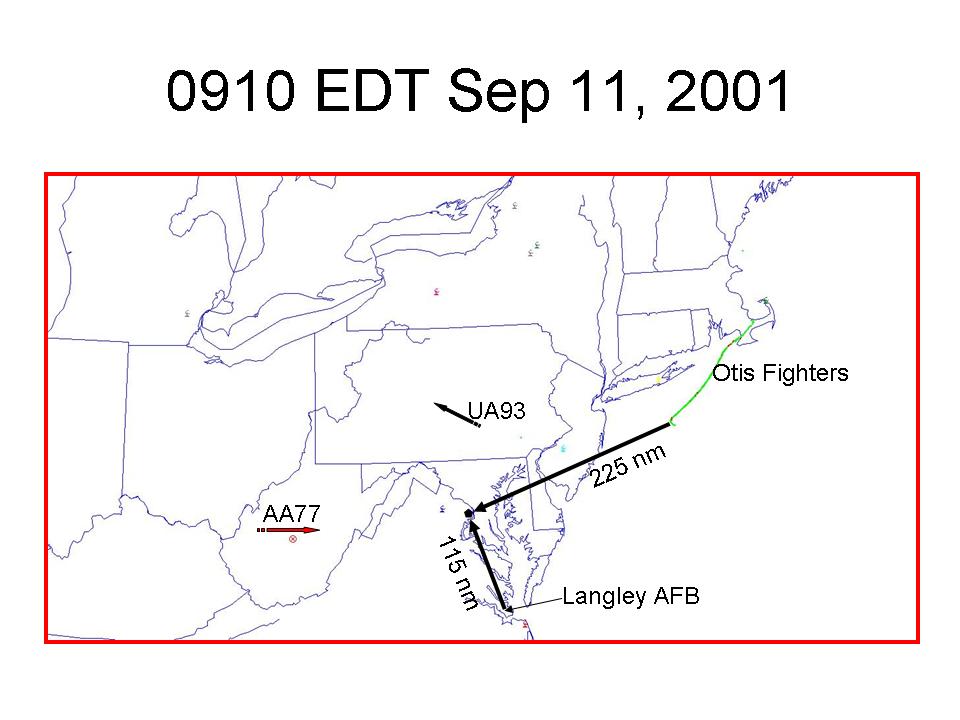

At that time, Indianapolis Center reported the loss of AA 77 to Great Lakes Region and the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center. NEADS made a critical tactical decision to keep Langley fighters on battle stations and not scramble. The Otis fighters had reached their closest point to Washington D.C. Most important, and undetected because no one cued NEADS, AA 77 was reacquired by the Joint Surveillance System supporting NEADS.

And that is what happened, or rather did not happen. From the attackers’ perspective the attack was over. Now, let’s add cascading bifurcation to the depiction and see what the defense was seeing and doing.

Cascading Bifurcation

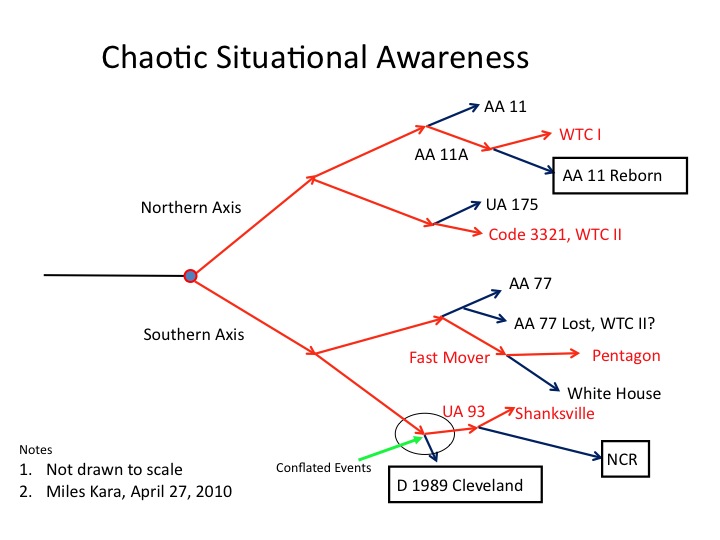

Here is the attack, as observed by the defenders. Situational awareness bifurcated in every case. Three of the four planes changed identities because of the terrorist tactic of manipulating the four transponders in four different ways. AA11 became AA11A, UA175 became code 3321, and AA77 became a fast-moving, non-transponding, intruder.

The tracks for AA 11 and UA 175 continued, notionally, on their original flight plans in the TSD system. AA 77 also continued notionally, on its original flight plan, and was also reported lost.

In the Northern attack, AA11 flew into the North WTC Tower, but became reborn to the defenders, most likely because of a garbled misunderstanding of the reported loss of AA 77. Mode C Intruder, 3321 (UA 175), flew into the South World Trade Center Tower.

In the Southern attack, the fast-moving unknown (AA 77), itself, became two threats, one to the Pentagon (actual) and one to the White House as perceived by air traffic controllers.

UA 93 was conflated with Delta 1989. That conflation continued in the aftermath. NEADS did establish a track on Delta 1989, the only viable track it established during the battle. Moreover, Delta 1989 was the only plane reported to be hijacked, by NORAD, in the national level Air Threat Conference. UA 93 crashed at Shanksville, a fact known at Cleveland Center, Herndon Center, NEADS, and Washington Center. That fact was reported to FAA Headquarters, but that is as far as national level awareness got. The track continued, notionally, in the TSD system and “landed” at Reagan National at 10:28. That was the track that Norman Mineta was following.

The national level did not sort out accurate information concerning AA 77 and UA 93. Therefore, those who testified to the 9/11 Commission in May 2003 (Corrected, April 22, 2015) 1993–Garvey, Mineta, McKinley– conflated information concerning UA 93 to apply to AA 77.

Three different threats–AA 11 reborn, the fast moving threat to the White House, a notional UA 93– became added “gain,” disruptive feedback, our next topic for discussion.

Disruptive Feedback

Feedback, in two cases, facilitated the counterattack, but became chaotic thereafter. The AA 11 reborn false report caused NORAD to launch the Langley fighters, but with an interim destination of Baltimore Washington International airport. The objective was to defend against an attack from the North against the nation’s capital. The threat, however, was fast approaching from the West; NEADS was unaware until the final moments.

The false Delta 1989 report caused NEADS to expand operations in the sector operations center. NEADS quickly acquired Delta 1989 as a track, which it followed continuously. The disruption came in the aftermath when NEADS conflated its tracking of Delta 1989 to pertain to UA 93.

The disruptive feedback of a notional UA 93 threatening the National Capital Region resulted in the launch of an expeditionary force, the Andrews fighters, into an existing air defense combat air patrol (CAP) established by NEADS using the Langley fighters. Chaos ensued as air traffic controllers and NEADS tried to sort things out. There were ultimately seven fighters in the CAP, three from Langley and four from Andrews. There was nothing against which to defend.

NORAD and the nation transitioned from that rough beginning to Operation Noble Eagle, a costly, nation-wide effort to patrol empty skies. Concurrently, staffs in the FAA and NORAD chains-of-command set about trying to figure out what had happened. The cascading bifurcation and disruptive feedback we have discussed were never figured out. Critical staff errors made at NEADS were never corrected. Therefore, the national explanation, itself, became a chaotic mess.

It was left to the 9/11 Commission to uncover that mess and get it sorted. During discovery, Team 8 Team Leader, John Farmer crafted a memo to the front office. There is no better description of what the Commission staff found and what the task was. Farmer wrote:

“In perhaps no aspect of the 9-11 attacks is the public record, as reflected in both news accounts and testimony before this Commission, so flatly at odds with the truth.” “The challenge in relating the history of one of the most chaotic days in our history…is to avoid replicating that chaos in writing about it.”

Chaos in the aftermath

Tsunami-like, is one way to describe the effect of the tidal wave of chaos that has swept the world since 9/11. Ted Koppel well described the state of affairs nearly five years ago. Here is what I wrote in 2010.

Ted Koppel

Today’s (Sep 12, 2010) Washington Post featured an above-the-fold editorial in the “Outlook” section by Ted Koppel; “Let’s stop playing into bin Laden’s hands.” At the end of the continuation, “Our overreaction to 9/11 continues,” Koppel posed a rhetorical question. “Could bin Laden in his wildest imaginings, have hoped to provoke greater chaos?”

Readers will pardon me from leaping ahead of my own story; that question by Koppel is too good to resist. (Koppel, as does nearly every other writer, researcher, and historian, uses the word “chaos” without definition.)

I need to speak to his use of the term in the context of his article, my own understanding of chaos, and my understanding of political revolutionary warfare.

As I am writing, David Gregory on “Meet the Press,” (Sep 12, 2010) is discussing the Koppel article with Rudy Giuliani. Gregory quotes Koppel extensively including the text: “Through the initial spending of a few hundred thousand dollars, training and then sacrificing 19 of his foot soldiers, bin Laden has watched [al Qaeda] turn into the most recognized international franchise since McDonald’s.”

My initial intent

It was, and remains, my intention to write a series of articles detailing the national level’s descent into chaos the morning of 9-11. I have posted an initial article depicting the friendly situation at 10:10, the time that Air Force One turned away from a return to the capital.

A paradigm shift

Koppel’s narrative is a game changer. He extends the chaos metaphor far beyond the events of 9-11 by stating that we have “played into bin Laden’s hands.” And that leads me to the subject of political revolutionary warfare.

My experience

For six years (1974-1980) I was the lead instructor and course manager for the Navy’s Counterinsurgency Orientation (COIN) course at the Naval Amphibious School, Coronado. During those six years we changed the focus of the course to revolutionary warfare. The course name changed as well to become a political revolutionary warfare seminar, “Political Warfare Studies.”

We developed a detailed framework to analyze revolutionary and political movements. I will write about that framework in the future. For those interested, I did address the framework in this thread on the Small Wars Council forum.

For now it is sufficient to simply state two things that are inherent in any qualitative revolutionary movement.

First, the goal of any revolutionary movement that knows what it is doing is to give the opposition every opportunity to believe in the myth of a military victory.

Second, in the words of Dr. Tom Grassey, Capt (USN-retired), one of our lecturers, an objective of revolutionaries is to encourage the status quo to “strangle in its own strength.” (Tom Grassey is the former James B. Stockdale Professor of Leadership and Ethics, Naval War College; and former Editor, Naval War College Review.)

Today, Ted Koppel said, “The goal of any organized terrorist attack is to goad a vastly more powerful enemy into an excessive response.” He is saying the same thing that Grassey articulated a quarter century ago.

Have we learned nothing? I will have much, much more to say.

Interested readers may want to review my article “Sudden an Eagle Tarnished,” for additional perspective.

Forward to the present

It has taken me five years to pull everything together in this article. Missing until recently was the clear understanding that the battle of 9/11 was a military action not a terrorist attack, one which triggered a massive military response that continues to this day, with no end in sight.

In our discussion of chaos and chaos theory we have learned that chaos can be bounded. That lesson was learned on 9/11 when Benedict Sliney and his staff at Herndon Center ordered all commercial aircraft to land. The lesson did not resonate at the national level, however.

Thereafter, national actions, specifically the invasion of Iraq, unleashed chaos in the Arab world. What began as an optimistic Arab Spring has bifurcated multiple times and out of that cascade the Islamic State emerged. Ultimately, a new order of things will emerge. Chaos will eventually bound itself; it must. And things will never be the way they were before.

Scholars far more learned will try to tell us about that, but it remains for historians well into the future to try and get the story right. Hopefully, they will do better than those in government who came up with a nonsensical account of the day of September 11, 2001.

Epilogue

So, we have come to the end of my main work that began with what I felt, heard, and saw when AA 77 slammed into the west side of the Pentagon. The road traveled was interesting, including staff assignments to both the Congressional Joint Inquiry and the 9/11 Commission.

There is remaining work to do on bits and pieces scattered here and there in my posts and pages. I will get at those loose ends at a leisurely pace. I will also continue to monitor things via a 9/11 Google Alert and post when the mood strikes.

Alert readers will know that I have left an interesting story yet untold, one that I promised to include in this article. Didn’t happen, but I will get around to it.

Amidst the near total chaos during the battle of 9/11 the Otis air defense fighters broke military formation and headed for New York City, leaving the nation’s capital undefended in the process. The question is did they do that on their own recognizance or were they ordered to do so? The definitive answer is lost in the fog of war and the chaos of the morning. But it is an interesting story that needs to be told.